Aug 14 2014

Making It Home: Is Reality a Café or a Baseball Diamond, Part 2

As I continue to unfold my analogy of rounding the bases of a baseball diamond as a representation of the logical steps one must proceed through to arrive at the correct religious position, please don’t misunderstand either this or my previous post. I’m not claiming to have proven anything yet.

Theoretically speaking, there might be no such thing as objective truth. Reason might not be able to reliably deduce anything. There might not be a Supreme Being like God. Christ might not be divine, but merely a man and no more. Or someone might accept the first point (the existence of objective truth), but not the second (the reliability of reason); or accept the first and second but not the third (the existence of God); or accept the first three but not the fourth (the deity of Christ).

I haven’t yet made arguments for any of the above. I’m simply sketching out the logical sequence in which those arguments need to be made, the order in which in fact they traditionally have been made. There’s no point, for example, in beginning by seeking to prove that Christ is God to someone who doesn’t believe that such a being as God exists. Likewise, there’s no point in arguing for the existence of God with someone who doesn’t believe in the validity of rational arguments, or believe in the existence of anything outside his or her own subjectivity.

I haven’t yet made arguments for any of the above. I’m simply sketching out the logical sequence in which those arguments need to be made, the order in which in fact they traditionally have been made. There’s no point, for example, in beginning by seeking to prove that Christ is God to someone who doesn’t believe that such a being as God exists. Likewise, there’s no point in arguing for the existence of God with someone who doesn’t believe in the validity of rational arguments, or believe in the existence of anything outside his or her own subjectivity.

(I say “his or her” out of deference to the current craze for always insisting on inclusive language, but in my experience it’s only been males who fall for the easily-refuted — in fact self-refuting — delusion that there is no such thing as objective reality that exists outside of ourselves. Women tend to be much more intelligent and intuitive than men on this point, and all women automatically accept that a whole world of objective reality exists outside of themselves, which is why women go shopping.)

(I say “his or her” out of deference to the current craze for always insisting on inclusive language, but in my experience it’s only been males who fall for the easily-refuted — in fact self-refuting — delusion that there is no such thing as objective reality that exists outside of ourselves. Women tend to be much more intelligent and intuitive than men on this point, and all women automatically accept that a whole world of objective reality exists outside of themselves, which is why women go shopping.)

(For the demonstration that the denial of objective reality is self-refuting, see the next — forthcoming — post in this series, “Do You Object to Objective Truth?”)

So back to our now-familiar baseball analogy. If the case for Christianity as the true theism (which we’ll be making in upcoming posts) successfully convinces us, we’ve made it to second base. But just as when we previously arrived at first base, we discover that the game’s not over yet. Just as on first base, there’s a confusing cacophony of voices on second base, all claiming to represent the Christianity we’ve come expecting to embrace. There are Quakers and Baptists and Pentecostals and Methodists, independent fundamentalists and Congregationalists and Disciples of Christ, Lutherans and Presbyterians and Anglicans, Greek Orthodox and Russian Orthodox and Catholics — to say nothing of the relatively recently-minted Christian sects (most of them “made in the USA”): Jehovah’s Witnesses and Mormons and Seventh-Day Adventists and still others. What do we do with these conflicting claims?

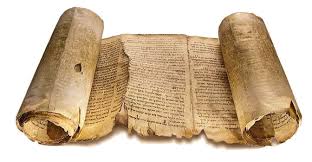

One obvious approach would be to study the original “founding documents” of Christianity (the books making up the New Testament), and perhaps the writings of the early Christians who received, reflected on, and taught the New Testament (the men we call the “early Church Fathers”), to ascertain what they believed. One would want to know what original Christianity looked like, and when and where other forms began to diverge from the original article — began to stray from the “straight and narrow” way.

One obvious approach would be to study the original “founding documents” of Christianity (the books making up the New Testament), and perhaps the writings of the early Christians who received, reflected on, and taught the New Testament (the men we call the “early Church Fathers”), to ascertain what they believed. One would want to know what original Christianity looked like, and when and where other forms began to diverge from the original article — began to stray from the “straight and narrow” way.

Protestantism (in its tens of thousands of varieties) claims that Catholicism (in the West) and Eastern Orthodoxy (in the East) represent this gradual divergence from the original Faith, until having crossed a line they collapsed into a contaminated mess of medieval superstition that was no longer faithful to Scripture, and that Protestantism was, beginning 500 years ago, a recovery of the pristine purity of the gospel (the “good news” of the Christian message), which obliged it to break away from the rottenness of Roman Catholicism in the Western Church.

That’s a position I well understand, having held it with fierce conviction for 14 years, from the age of 14 to the age of 28. (The first 14 years of my life I was raised in, and professed, no form of Christianity, either Protestant or Catholic, or any other religious faith, for that matter.) When I became a fervent Protestant as a freshman in high school, I discovered and made my own the attitude toward Roman Catholicism expressed by the original Protestant Reformers: Luther, Calvin, Zwingli, Thomas Cranmer, and others.

Catholics, of course, take a very different view of the matter. (To be continued)